My Chess Project Is Finally Over…

This semester has flown by, and so has this learning project! As part of ECMP 355, a class about using technology in the classroom, I was required to use online sources to learn a skill of my choice and to blog about it weekly to share my progress.

I chose to learn how to play chess because it was a skill I had very limited experience with and I thought it would be nice to have something completely different to work on that still counted as homework. I also felt chess was a solid choice because it is one of my fiancé’s passions, so I knew he would be able to direct me to useful online sources and support me in the process.

So I bet you’re wondering how my epic chess quest turned out. Was it a nice break from homework? Not at all. Was my fiancé helpful and supportive? Absolutely. Does that mean I enjoyed the process? Not a chance. This project really challenged me, and although I definitely feel I’ve grown in my chess abilities, I can’t say I enjoyed the whole process.

Now my negativity has you hooked! Check out this recap of my learning project posts to find out more about the ups and downs of my journey:

Learning Project Recap

- Introduction, inspiration, and rationale for my learning project

The Opening (of my epic chess quest)

- Explaining initial resources: Chess.com, tactics puzzles, and YouTube videos including Everything You Need To Know About Chess: The Opening

- Comparing myself to a frustrated baby elephant after losing games

Valiant Knight Crushed in Grueling Battle (My First Chess Tournament)

- Narrative of my experience at a chess tournament put on by the Queen City Chess Club on January 16th

- (How I got beat by an 8-year-old)

Dropped Pieces + Shattered Dreams = Fresh Determination

- Describing challenges: finding motivation to play chess games when busy/tired, dropping pieces in my games

- Video where I analyze one of my online games

- New action plan: play and analyze 4 games/week, continue doing tactics puzzles every day, watching instructional videos and live streams more often

- Tools to share learning: Screencastify

Chess Cognition (AKA Thought Process Boot Camp)

- Description and key learnings from Chess Cognition video series by John Bartholomew

- What I liked and didn’t like about this video series

- Identifying specific chess skills to work on

Chess Games: The Ultimate Relationship Test

- Picture and cheesy fast-motion video of me playing chess against my fiancé, Kelly, to show my progress

- Video of our joint game analysis (with highlights provided) to show my progress and teach others about chess skills

- Tools used to share learning: Samsung video editor app (recommended by Curtis), phone tripod (borrowed from Curtis)

S’more Chess Updates (not the graham cracker kind)

- Description of key take-aways from instructional videos including Climbing the Rating Ladder: Up to 1000 and Chess Fundamentals #1: Undefended Pieces

- Recent online games embedded (you can go click through the moves of my game) with brief analysis

- Stats including game record, daily tactics activity, and tactics performance

- Tool used to share learning: Smore

Tried-and-True Resources to Help You Learn Chess

- Annotated collection of resources I have used to improve my chess game

- Tool used to share learning: Padlet

One Assessment of My Learning

It’s kind of tricky to show my level of mastery now vs. when I started this project. My Chess.com started me with a provisional rating of 1200, so I had to keep losing games until my rating became more accurate. My rating is now 980, and I’m still not sure how accurate that is.

One aspect I saw definite progress in was my tactics! My goal was to reach a rating of 700 on my tactics, and I achieved that on April 4th! Here is a chart that shows my tactics ratings over the past three months:

Reflections on the Process of Learning Online

What does learning online make possible?

- The ability to express frustrated and/or angry reactions without fear of being judged.

This was a huge difference I found between playing chess online and playing chess in person at the chess tournament. When playing online, I could moan, groan, pout, or yell at my computer screen without worrying about what my opponent would think of these (over)reactions. When I played in the chess tournament, I had to keep my emotions in check and be polite and courteous at all times.

My face after every chess game…

Photo Credit: Scott SM via Compfight cc

2. The ability to play a chess game with little to no social interaction with your opponent.

This might sound like a negative thing, but I appreciated having no social interaction with my online opponents. At the tournament, I was annoyed at receiving a comment about my appearance, distracted by my opponents’ facial expressions during the game, and embarrassed to be seen losing to an 8-year-old. When I played online, I didn’t have to worry about any of those kinds of things.

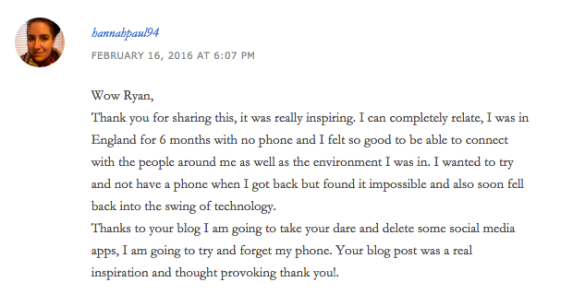

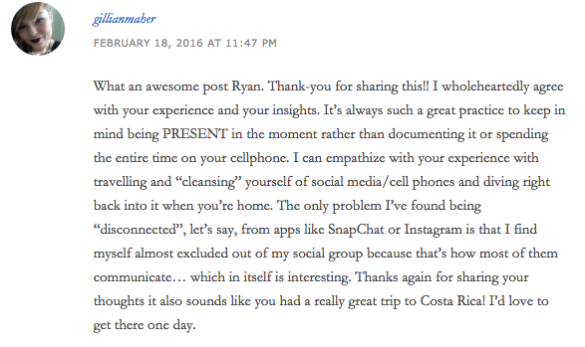

3. The ability to receive feedback and encouragement from others on your learning.

I received encouragement from classmates and people outside the class on my learning project:

I also received feedback on the ways I chose to share my learning project:

4. The ability to learn from and feel connected to experts who are far away from you.

Had I not used YouTube as one of the main sources for my learning, I would not have been able to learn from International Master Daniel Rensch or International Master John Bartholomew, who are both professional players and coaches. I also found that after I watched several of their videos, I started to feel like I knew them personally.

What might the process of learning online make impossible?

- Private one-on-one learning sessions with another person.

Choosing to learn a skill online usually means that you learn from a variety of sources, which might reduce the possibilities for intimate learning sessions and one-on-one relationship-building with a teacher. For example, if I had learned piano from online sources rather than through private lessons growing up, I wouldn’t have developed such a close relationship with my auntie/piano teacher.

2. Using all the free time you have to focus on learning the skill.

The process of sharing about your learning can be time consuming. Throughout this project, I sometimes felt like I was spending just as much time writing blog posts about learning to play chess as I was actually learning to play chess.

I can’t think of anything else that learning online makes impossible. Feel free to drop me a comment if you have any ideas!

Final Thoughts

My biggest challenge throughout this learning project was getting frustrated when I lost games. I took my losses really personally, especially at the beginning of my project. As I began to learn more about chess, I discovered how technical it is and found that even really talented players can learn sometime from each game they play. After my losses, I had to constantly remind myself to say “I made this mistake” instead of “I suck at chess,” which was something I really struggled with.

I think the negative self-talk I fell into often happens to students in the classroom when they make mistakes. When I have my own classroom, I really want to emphasize that it’s okay to make mistakes and that mistakes are a necessary part of the learning process. This is definitely easier to say than to put into practice, but I think I could share the story of this learning project with my students to show them how negative self-talk detracts from learning and how adults also struggle with it.

I definitely see the benefits of learning a skill online and sharing that process with the world. Through this project, I was able to: learn from and critically evaluate a variety of online resources; share my progress openly through my blog and Twitter using the hashtag #learningproject; receive encouragement and feedback from my PLN; and explore new tech tools to document my learning. Although attempting to learn chess was challenging, I’m glad I took it on and I think I learned a lot more than chess skills from this project.